Music and politics have both been a huge part of my life from a young age. My dad is an avid music lover and concert goer, and some of my earliest memories are listening to CDs with him on the car ride to preschool. I started regularly going to concerts with my dad when I got a little older and we still go to shows together to this day. Politics have also been central in my upbringing. Another core memory I have from my early childhood is going with my mom when she voted in the 2004 presidential election. I was not even three years old, yet I was fascinated with the voting process and could not wait to do it myself when I turned 18. In 2008, when Barack Obama was elected president, I was only six years old, yet I was euphoric. Throughout the remainder of my time in elementary school, I actively followed political campaigns, elections, and even ran for student council to feel more involved in the democratic process. Today, I still hold the same passions, as I am majoring in political science with plans to go to law school. I am also a member of SCOPE Productions and regularly attend concerts and music festivals with my family and friends.

But I want to divert from the present for just a minute, and go back around ten years ago, when I began middle school. This is when my music taste started diversifying. I began listening to genres outside of the indie and alternative rock music my dad raised me on. I started listening to more rap, hip-hop, and R&B music, which led me to more Black music artists. I was intrigued by the poetic and rhythmic elements of rap and hip-hop, and the meaningful lyricism was an added bonus.

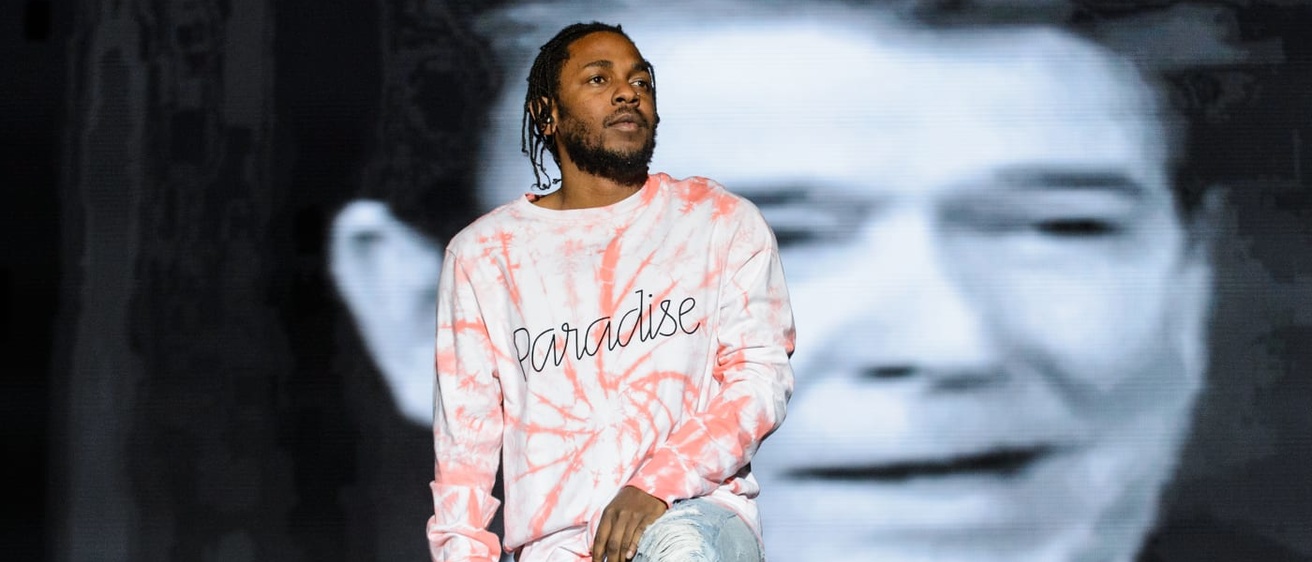

One of my favorite artists in the rap genre is Kendrick Lamar – his music has been on repeat for me for the past few months. While listening to his music over and over while driving long distances or getting ready in the morning, I began to realize the depth and breadth of his lyrics. He uses incredible rhythmic, poetic, and musical elements within his work, but he also addresses critical issues. His lyrics not only feature his own personal and political experiences as a Black man, but they also mention broader Black history and Black social and political issues in the United States.

Aside from Kendrick Lamar, there are many other artists who have released similar work that feature political and social references. Prominent groups and artists like N.W.A and Public Enemy are considered to be rather pioneers in involving social and political issues in their music. N.W.A is one of the early major music groups that outwardly addressed and condemned police violence against Black men through their music. I have noticed mentions of political and social issues facing Black Americans, as well as Black history, in music by artists like Anderson .Paak, Baby Keem, JAY-Z, Kanye West, Big Sean, and Childish Gambino. For simplicity’s sake, I want to focus on the lyrics in three songs by Kendrick Lamar that directly reference Black history and Black social and political struggles.

Throughout Lamar’s eight albums, there are dozens of songs peppered with lyrics addressing social and political struggles that he faced, similar to the experiences of many young Black men. His debut album, Section.80, features a song titled “Ronald Reagan Era”. The duration of this song addresses the war on drugs that was spearheaded by former President Ronald Reagan in the 1980s. Lamar references this with the verses, “this sound like 30 keys under the Compton court building, hope the dogs don’t smell it, welcome to vigilante, 80’s so don’t you ask me.” Within these lines of the song, Lamar acknowledges the presence of large quantities of drugs in neighborhoods like Compton during the 1980s – this was due to the war on drugs. This was a racially motivated effort by Reagan to cause drug addiction issues in Black neighborhoods and subsequently criminalize, incarcerate, and impoverish Black Americans. Within the song, Lamar talks about violent acts of racism towards Black residents, increased police presence in Black neighborhoods, and the pervasive criminal justice system.

Lamar’s debut album also features an opening track titled “F*ck Your Ethnicity”. Some early lyrics of the song are Lamar saying, “Now I don’t give a fuck if you Black, white, Asian, Hispanic, goddammit, that don’t mean shit to me”. Lamar essentially says that he does not support differential treatment towards someone based on their race or ethnicity, that racism is a ridiculous concept. He also notes that although we live in the 21st century where racism is supposedly nonexistent, this is far from the truth, “racism is still alive, yellow tape and colored lines”. Within two verses in his song, Lamar addresses de facto and de jure racism and segregation, specifically how de facto racism has morphed into de jure racism. De facto refers to individual actions that are racially motivated and seek to exclude and segregate others. De jure segregation is the racially motivated exclusionary practices carried out through government institutions and policy. In this song, Lamar references de facto racism and segregation when he expresses his indifference towards people of various ethnicities or races. Lamar connects the two forms of racism and segregation when he says, “racism is still alive, yellow tape and colored lines.” He is absolutely correct – racism is still alive and present through systemic and institutional policies and practices. The yellow tape, referring to police presence and response, is a crucial example of racism within the justice system and government institutions. Colored lines, referring to the racial segregation of neighborhoods and community spaces, also reflects the influence de facto racism has had in spurring de jure racism. Redlining is a historical practice that was initially used by the National Association of Real Estate Boards and then adopted by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) in 1935. The FHA divided cities into neighborhoods of varying degrees of “risk” – areas that were deemed to be “high risk” or “hazardous” were mostly neighborhoods of Black and Brown families. Financial lending institutions that issued loans for homebuyers were instructed not to supply loans to residents who were looking to purchase a home in the “hazardous” areas. This led to catastrophic housing, income, and wealth inequality, especially for Black and Brown Americans. Redlining is now illegal, and is allegedly no longer practiced, but future homeowners still face forms of discrimination through de facto measures. This ranges from real estate agents denying offers made by Black and Brown home buyers, denial of home loans from financial institutions based on personal prejudices, and being treated with disdain and malice by white neighbors.

Another predatory practice by housing agencies was blockbusting, which involves sparking racial panic among white residents. Representatives from home buying or real estate agencies would “warn” white residents that Black and Brown families were moving into their neighborhoods, which they stated would consequently lower their home value and environmental quality. These housing agencies would buy homes of white residents fleeing to the suburbs at a low rate, and then sell the homes to Black and Brown residents at above market rates, usually binding them to contractual payment methods. This created financial instability in neighborhoods and led to municipal governments and law enforcement inappropriately targeting area residents. Lamar is from Compton, California, which became a neighborhood composed of mostly Black residents in the 1970s as a result of block busting tactics. Throughout dozens of his songs, Lamar references common stigmas, stereotypes, and attitudes applied to Compton, given that the city experiences high poverty rates and the majority of the residents are Black.

One of Lamar’s most popular songs, “King Kunta”, is featured on what is considered to be an essential album of his, To Pimp a Butterfly. This is easily one of my favorite songs, due to its upbeat rhythm, the flow of the lyrics, and also the content of the lyrics themselves. Lamar discusses many aspects of political issues both past and present that Black Americans, especially Black men, have experienced. One of my favorite lyrics from the song is, “what you want? A house or a car? Forty acres and a mule, a piano, a guitar?” I had to do a double take while listening to this for the first time – I was surprised that Lamar had explicitly mentioned the 40 acres and a mule, or Field Order 15 plan. During the reconstruction era following the civil war, Union General William T. Sherman proposed providing all Black American families with 40 acres of their own land, along with a mule. He believed if they were able to own and farm their own land, this would initiate financial security and a stable livelihood for these families in the aftermath of the war. This plan was rolled into effect while former President Abraham Lincoln was in office, however, upon his assassination, when former President Andrew Johnson took over, the order was rescinded and the land was returned to its former confederate owners. This order was one of the first concrete examples of reparations for Black Americans in the United States. It’s difficult to say what America would look like to this day if the order would have remained in place, however, it is inspiring to know that reparations for Black Americans are not a novel concept and could very much be implemented today.

To me, Kendrick Lamar’s efforts to address past and current social and political issues affecting Black Americans within his award-winning music is invaluable. It leaves me speechless, but it conjures many emotions for me, mostly admiration, gratitude, and pride. It is so important that someone with a platform as large as Lamar’s is creatively and meaningfully addressing important social justice issues. Although it may sound cliche, it is absolutely beautiful the way Lamar intertwines both his own personal and shared experiences as a Black American man within his music. Like many forms of art created by Black artists, Lamar’s music weaves together concepts of vulnerability and empowerment. It is riveting and inspirational – it brings a call to action and reassurance to keep investing in the fight – perfectly aligning with the goals of Black History Month.

Photo from Complex